The tree is perhaps one of the most powerful symbols possible, evoking meaning and emotion in cultures across the world. From the symbolism of the olive branch to that of the mighty oak, from the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden to one’s own family tree, it is hard to deny the influence of the arboreal.

It is unsurprising, then, that so many artists have made use of trees in their work. Whether as a focus of the piece in their own right, as part of a wider landscape or even as a complement to portraiture, trees are rooted firmly in artistic history.

Left, George Weissbort, Forest clearing, Vienna, 1952.

Left, George Weissbort, Forest clearing, Vienna, 1952.

Right, Vanessa Garwood, Spain: Trees & Shadows.

For those without an artistic bent, the tree might seem to be an overly simple subject. However, to the artistic eye, they offer a fascinating, lively and challenging subject. In 1889, Vincent van Gogh completed at least 18 paintings of olive trees, which are ranked amongst his finest works. He wrote to his brother Theo of his struggle to capture the trees, and found that the “rustle of the olive grove has something very secret in it, and immensely old. It is too beautiful for us to dare to paint it or to be able to imagine it.”

However, he did dare, and many others have also dared to focus their artwork on trees. George Weissbort’s Forest clearing, Vienna, 1952 evokes a clear, sunshine-filled day, the brightness of the colours catching the ephemeral nature of both sun and leaf. Vanessa Garwood’s Spain: Trees & Shadows uses a close focus on a group of trees to evoke a complex and almost maze-like perspective; the trees not only create the shade but populate it with a vibrant sense of life.

Left, Fergus O’Ryan, The Liffey at Sally Gap, 1928.

Left, Fergus O’Ryan, The Liffey at Sally Gap, 1928.

Right, Sigvard Hansen, Bøgholm Lake in autumn.

In landscape paintings, trees often serve as vital compositional features, giving structure and form to a natural scene. In both of the examples above, the trees are used to take advantage of the Rule of Thirds, standing tall as an offset point of interest which creates a sense of lateral movement, complementing the flow of the water.

Trees are also frequently used as repoussoir devices; set in the foreground to one side of the composition, bracketing or framing the image and drawing the viewer’s eye into the piece. This is particularly common in 17th century Dutch paintings, exemplified by the works of Jacob van Ruisdael.

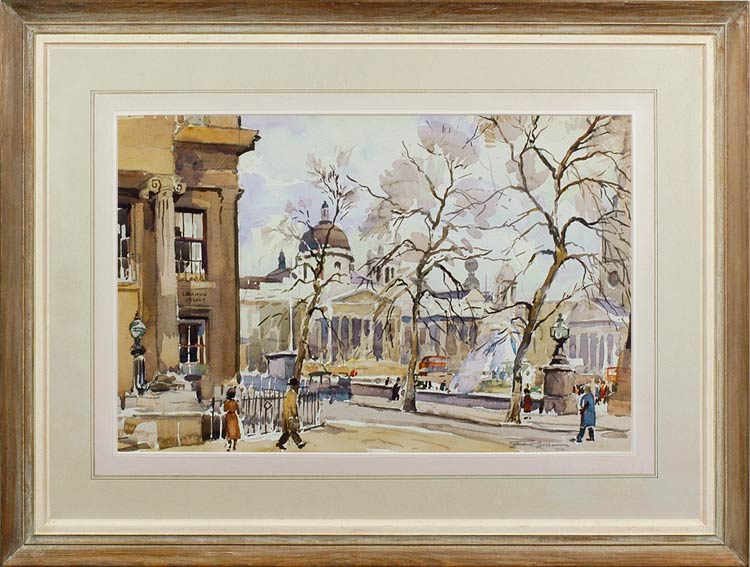

Edward Wesson, Trafalgar Square looking towards the National Gallery from Canada House, 1950.

In Edward Wesson’s Trafalgar Square looking towards the National Gallery from Canada House, the repoussoir is instead provided by the solid corner of Canada House, but even in this urban scene the trees play a vital part. The bare plane trees of the square appear to march across the piece, the sloping angle of their tops drawing the eye towards the National Gallery in the distance. Their skeletal forms help to give shape to the landscape as well as evoking the brisk bustle of a city in winter.

In an increasingly urbanised world, art can often serve to bring us closer to nature; we may not all have the space to grow our own trees, but we can possess and preserve them through the eyes of the artist.